The Lewis’s woodpecker’s common and scientific names pay tribute to the famed explorer Meriwether Lewis, who with his partner, William Clark, explored the American West.

The 215th anniversary of the launch of the famous Lewis and Clark Expedition will be observed May 14. Also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, the enterprise became the first American expedition to cross the western portion of the United States and explore the recently acquired lands known collectively as the Louisiana Purchase. The Lewis and Clark expedition officially extended from May 14, 1804, to Sept. 23, 1806. As they drove deep into the American West, the members of the expedition saw wonders, including the feathered variety, never before beheld by people outside of various Native American tribes.

In authorizing the expedition, President Thomas Jefferson wanted to establish a reliable route for travel through the western half of the nation and to fend off any attempts by European nations to gain a foothold beyond the nation’s frontier. Jefferson also hoped Meriwether Lewis and William Clark would make some important discoveries about the nation’s native fauna and flora. Jefferson gave instructions for Lewis and Clark to collect bones they found during their journeys. He also asked them to keep alert for large animals that would be new to science. In particular, Jefferson hoped that the men he chose to head the expedition would help prove that the American mastodon still roamed the American West.

Mastodon bones had been found in the eastern half of the United States early in the nation’s history. Jefferson, accepting the widely held view of his time that God would not let animals go extinct, entertained the optimistic belief that large herbivores such as the bison of the American West roamed portions of the newly-acquired Louisiana Purchase along with American mastodons. The expedition failed to find great herds of American mastodons trumpeting their way across the vast prairies and grasslands of the Western United States. As any student of history knows, however, the expedition made many important biological discoveries ranging from unique animals as the pronghorn antelope and grizzly bear to various fish, reptiles and plants.

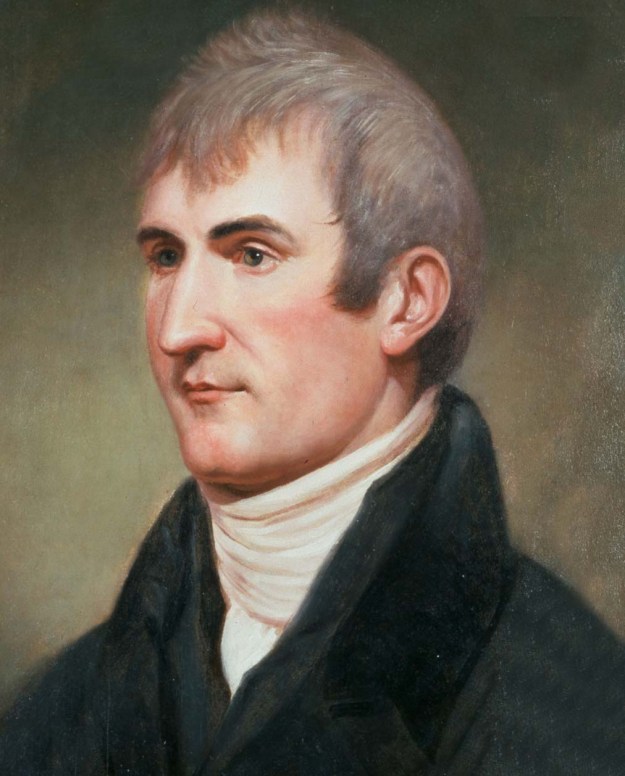

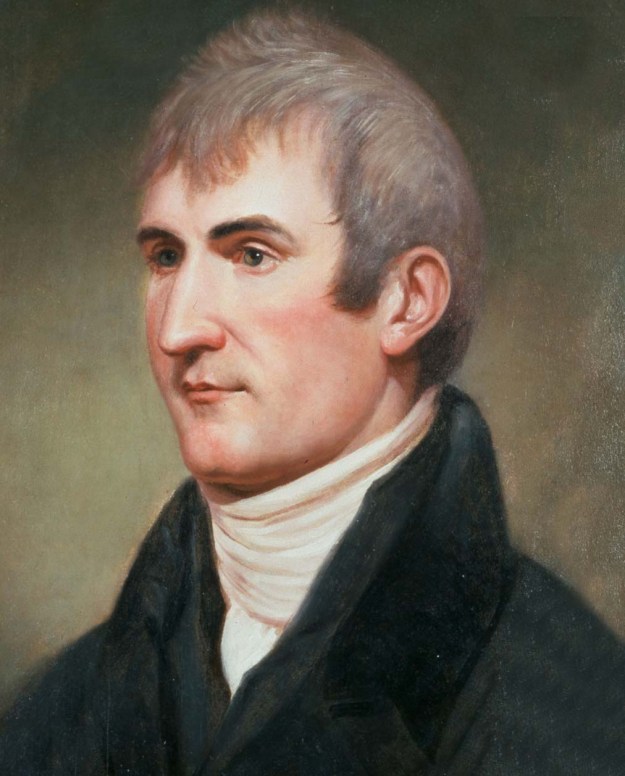

Meriwether Lewis gave his name to the famous Lewis and Clark Expedition. as well as to the woodpecker named Lewis’s woodpecker.

The expedition also described nearly half a dozen species of birds that, at the time, had never been discovered and detailed by European Americans. These birds included the common poorwill and the greater sage-grouse. One of the birds — Lewis’s woodpecker — even memorializes the name of Meriwether Lewis and his important contributions to the success of the venture.

Lewis described the woodpecker that now bears his name as a bird “new to science” in one of his journal entries dated May 27, 1806. He made his observations of the bird while the expedition camped on the Clearwater River in what is now known as Kamiah, Idaho. He had mentioned the “black woodpecker” in earlier accounts in his journal, but during his time in the Idaho camp, he managed to shoot and preserve several of the birds. In his account, he described the bird’s behavior as similar to the red-headed woodpecker of the Atlantic states back in the eastern United States.

As it turns out, both Lewis’s woodpecker and the red-headed woodpecker belong to the Melanerpes genus of woodpeckers, which also includes about two dozen species ranging North and South America, as well as the islands of the Caribbean. The other members of the genus found in the United States include acorn woodpecker, gila woodpecker and red-bellied woodpecker. The term Melanerpes comes from ancient Greek words for black (melas) and creeper (herpes), which roughly translates as “black creeper.” Lewis’s woodpecker, one of the largest of its kind found in the United States, can reach a length of 10 to 11 inches. In 1811, the famous naturalist Alexander Wilson composed the first description of the bird for science and named it Melanerpes lewis after Meriwether Lewis. In addition, the bird’s common name has always identified it as Lewis’s woodpecker.

Photo by Dave Menke/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service • Lewis’s woodpecker is found primarily in the west. It eats insects, mostly caught in the air, as well as fruits and nuts. The woodpecker also shells and stores acorns in the bark of trees.

These woodpeckers nest in open ponderosa pine forests and burned forests with a high density of standing dead trees. They also breed in woodlands near streams, oak woodlands, orchards, and pinyon-juniper woodlands. In appearance, Lewis’s woodpecker stands out from other American woodpeckers. Its unique appearance includes a pink belly, gray collar and dark green back, quite unlike any other member of its family. In behavior, it also differs from other woodpeckers. This woodpecker is fond of flycatching, perching on bare branches or poles and then making flight sallies to capture winged insect prey. It has also been described as flying more like a crow than a woodpecker.

We haven’t been good stewards of the woodpecker that the famous Expedition brought to our notice. According to the organization Partners in Flight, Lewis’s Woodpeckers are uncommon and declining. Their populations declined by 72 percent between 1970 and 2014. Lewis’s Woodpeckers are threatened by changing forest conditions as a result of fire suppression, grazing and logging. These factors often leave pines of a uniform age in the woodpecker’s favored habitat and fewer of the dead and decaying pines crucial for the bird’s nesting success. Humans could help Lewis’s woodpecker thrive by not removing dead or dying trees from western forests.

After the Lewis and Clark Expedition returned to the eastern United States and reported back to Jefferson, he was awarded with 1,600 acres of land. He meant to work on publishing the journals he kept during the Expedition, but kept finding himself distracted. In 1807, Jefferson appointed Lewis governor over the Louisiana Territory that Lewis and Clark had so famously explored. He governed the territory from the Missouri city of St. Louis, which became known as the “Gateway to the West” as more Americans expanded into the territory they had learned about thanks to the famous Expedition.

Meriwether Lewis in a pose painted with him wearing garb he chose for the expedition.

Lewis spent two troubled years trying to administrate the new territory, but he became entangled in political squabbles and financial difficulties. Things got so difficult for him that Lewis decided he needed to travel to the nation’s capital in person to clear up the mess. On his way to Washington, D.C., he stopped at an inn along the Natchez Trace about seventy miles southwest of Nashville. He died of gunshot wounds on Oct. 11, 1809, and historians have debated ever since whether his death resulted from suicide or murder. Regardless of the nature of his demise, he earned a place in the history books. He’s also remembered every time a birder lays eyes on the woodpecker that bears his name. When the bird is researched in a field guide or on a web page, the more curious individuals are sure to dig a little deeper to learn who provided the Lewis in the woodpecker’s name. His name will continue to be recalled as long as this unusual western woodpecker continues to fly in its beloved pine forests.

I’ve never seen a Lewis’s woodpecker, although I have visited Utah twice to make the attempt. Lewis’s woodpecker is listed as an uncommon permanent resident on the state checklist, so perhaps I will need to be more diligent the next time I visit its home range. I see the red-bellied woodpecker, a smaller relative of Lewis’s woodpecker, on a regular basis. This common bird more closely resembles what most people expect a woodpecker to look like, and it will visit feeders for such fare as sunflower seeds, peanuts and suet.

Photo by Bryan Stevens • The red-bellied woodpecker is a close relative to Lewis’s woodpecker.

In next week’s column, I’ll continue my anniversary tribute to the Lewis and Clark Expedition with a discussion of the bird that honors William Clark, the other partner in the famous westward expedition of discovery.

Readers continue to share hummingbird tales

Garry Cole sent me an email recently to share a hummingbird story.

“I have been following the progress of hummingbird sightings as the birds moved closer to East Tennessee,” Garry wrote. “I read with envy how neighbors all around me had seen these jewels, but none had visited my home here in Hickory Tree near Bluff City.”

Then, on April 23, as Garry sat in the yard, a male ruby- throated hummingbird stopped and hovered less than a foot in front of his face.

“He looked me squarely in the eye as if to say, ‘Well, I’m here. When are you going to feed me?’”

Garry noted that the bird arrived at about 8:15 p.m. “I immediately went inside and prepared my feeder,” he said. “Now, I have at least four that visit my feeder every day. There may be more, but I have only seen four at one time.”

His hummingbirds drink about eight ounces of sugar mix every two or three days and seem to feed more frequently between 5 and 7 p.m.

Tom Brake shared via Facebook that hummingbirds have also returned to his home on Peaceful Valley Road in Abingdon, Virginia. In his posting to my Facebook page, he informed me that he had his first hummingbird sighting of spring on April 28.

Myra Harris message me on Facebook to let me know her mom, Mae Bell Byrd, who lives in Flag Pond in Unicoi County, Tennessee, saw her first hummingbird on April 12.

Photo by Bryan Stevens • Welcoming back hummingbirds also involves making sure that they remain healthy and safe while spending the next six months in our yards and gardens.