Sharp-eared birders may be detecting some unfamiliar crow calls in downtown Erwin during strolls around town.

While the caws of American crows are rather harsh and raucous to the ear, the smaller and related fish crow has a caw with a higher, more nasal tone that is just different enough to stand out.

Fish crows have been expanding their presence in the region for several years, joining some other newcomers such as common mergansers and Eurasian collared doves.

The fish crow is a native species of the southeastern United States that has been pushing its range farther north and west.

I first got to know fish crows on visits to coastal South Carolina starting in the 1990s. These small crows can be quite abundant along the coastline of the Palmetto State.

It’s only been in the last six years that I’ve added fish crow to my list of birds observed in my home state.

I began to hear fish crows around the campus of East Tennessee State University in Johnson City during daily strolls while teaching in the literature and language department at ETSU back in late fall of 2018.

For months before that sighting, I’d begun to notice postings about the presence of fish crows on the campus of the Mountain Home Veterans Administration adjacent to the ETSU campus. I’d heard about the fish crows from some of my birding friends, too. I had not stirred myself to look for these slightly smaller relatives of the American crow. So, when I heard a familiar “caw” that was a bit too nasal for an American crow, I stopped for a closer look.

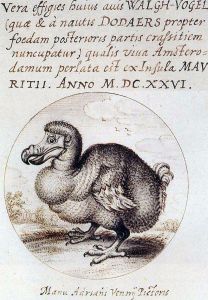

Photo by Pixabay • The American crow, pictured, is larger than the related fish crow and has a more raucous caw.

I heard the vocalizations again and found a couple of fish crows perched atop the parking garage behind the Carnegie Hotel, which is located between ETSU and the VA campus. With some surprise and delight, I realized that the birds were fish crows.

Fast-forward six years. In recent weeks I’ve been hearing fish crows in downtown Erwin on a fairly regular basis. This past week I heard the nasally caw of this crow as I approached the back door of the offices of The Erwin Record. I looked up and spotted a fish crow perched in one of the trees bordering the parking lot. I wonder how long before I get one of these small crows paying a visit to the fish pond at my home.

As I mentioned earlier, I’m familiar with fish crows from trips to coastal South Carolina, where these members of the corvid family are quite common. Fish crows have expanded inland away from coastal areas in recent decades. Fish crows showing up here in Northeast Tennessee originated from that expansion, which likely followed river systems like the Tennessee River.

The easiest way to detect a fish crow’s presence is to keep your ears open. Fish crows make a distinctive vocalization that is quite different from the typical “caw” of an American crow or the harsh croak of a common raven. The website All About Birds describes the call as a “distinctive caw that is short, nasal and quite different-sounding from an American crow.”

The website also makes note of the fact that the call is sometimes doubled-up with an inflection similar to someone saying “uh-uh.”

Although their name suggests a fondness for fish, they’re not finicky about their food and will eat about anything they can swallow. Fish crows are also known for raiding nests to steal the eggs of other birds. They will also dig up sea turtle eggs, which are buried in sand dunes by female turtles.

Fish crows don’t scruple at stealing food from other birds and have been observed harassing birds ranging from gulls to ospreys. Fish crows also harass American crows and, if they are successful, don’t hesitate to skedaddle with any morsel that they’re able to “persuade” their slightly larger relative to surrender.

The fish crow ranges in various coastal and wetland habitats along the eastern seaboard from Rhode Island south to Key West, and west along the northern coastline of the Gulf of Mexico.

It’s been fun to find these birds closer to home in Erwin and Johnson City.

It’s not been easy for crows in recent years. The West Nile virus has been particularly hard on American crows, which seem to have very little immunity to this mosquito-spread disease.

According to the research I’ve conduced, the fish crow, however, is more resistant to the virus, with close to half the birds exposed to the disease able to shake off the effects and fully recover.

According to the website Tennessee Watchable Wildlife, the first recorded sighting of a fish crow in Tennessee took place in 1931. Half a century later, the first nest record was documented in 1980. Both of these records took place in Shelby County.

The oldest known fish crow in the wild reached an age of 14 years 6 months old. Visit tnwatchablewildlife.com for more information about fish crows and other state birds.

Fish crows and other crows around the world are sometimes regarded more darkly than is usual for our fine feathered friends. We invent lore and superstition, mostly inspired by the crow’s dark plumage and some rather unsavory eating habits. Some people even consider crows a bad omen.

I’ve never been concerned personally with keeping crows, or any bird for that matter, at a distance. I always try to stay alert for any surprise these winged creatures bring my way.

Worldwide, there are about 50 species of crows in the Corvus genus. Some other crows include carrion crow, hooded crow, rook, small crow, white-necked crow, Eastern jungle crow, large-billed crow, violet crow and white-billed crow.

Why have fish crows expanded their range in recent decades? The answer is not clear, but it’s good to have them here. I’m glad to welcome them to the Valley Beautiful.

•••

To share a sighting, make a comment or ask a question, email me at ahoodedwarbler@aol.com.