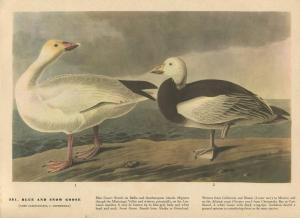

Contributed Photo by Joe McGuiness • A visiting snow goose stands by the edge of a Unicoi pond as a nearby Canada goose preens its feathers. Snow geese are known for two color phases: white and blue. This particular goose appears to have characteristics of both color phases.

I was left a phone message on the first day of December by Erwin resident Joe McGuiness, who is also a fellow member of the Elizabethton Bird Club.

Joe wanted to let me know about an unusual goose that had been present at a farm pond along Massachusetts Avenue in Unicoi.

He had already identified the bird as a snow goose, which has two distinct coloration phases: the namesake white phase and a dark phase known as a “blue goose.”

The problem with this particular goose was that it seemed to show characteristics of a typical snow goose and a “blue” goose.

“Based on the fact that it has a white belly, I think this is a retrograde between a white phase and blue phase of the snow goose,” Joe wrote in a followup email.

“Not a true blue phase of the snow goose,” he determined. Based on my own observation, I concurred with his assessment.

The visiting snow goose has been hanging out with a flock of Canada geese that move from the pond to some nearby fields.

Of the geese found in the region, the well-known Canada goose is nearly ubiquitous. Surprisingly, that’s not always been the case. For instance, in his book, “The Birds of Northeast Tennessee,” Rick Knight points out that the Canada geese now present throughout the year resulted from stocking programs conducted in the 1970s and 1980s. In earlier decades, the Canada goose was considered a rare winter visitor to the region. Seeing the Canada goose in every sort of habitat from golf courses to grassy margins along city walking trails, it’s hard to imagine a time when this goose wasn’t one of the region’s most common waterfowl.

Photo by Bryan Stevens • A snow goose swims amid Canada geese a few years ago at the pond at Fishery Park in Erwin, Tennessee.

The world’s geese are not as numerous as ducks, but there are still about 20 species of geese worldwide, compared to about 120 species of ducks. While both ducks and geese are lumped together as waterfowl, most geese are more terrestrial than ducks. Birders are just as likely to spot geese in a pasture or on the greens of a golf course as they are on a lake or pond.

The snow goose breeds in regions in the far north, including Alaska, Canada, Greenland and even the northeastern tip of Siberia. They may spend the winter as far south as Texas and Mexico, although some will migrate no farther than southwestern British Columbia in Canada.

The snow goose bucks the trends that show many species of waterfowl declining. Recent surveys show that the population of the snow goose exceeds five million birds, which is an increase of more than 300 percent since the mid-1970s. In fact, this goose is thriving to such a degree that the large population has begun to inflict damage on its breeding habitat in some tundra regions.

A smaller relative to the snow goose is the Ross’s goose, which for all practical purposes looks like a snow goose in miniature. The common name of this goose honors Bernard R. Ross, who was associated with the Hudson’s Bay Company in Canada’s Northwest Territories.

Here’s a quick history lesson. Hudson’s Bay Company is the oldest commercial corporation in North America. The company has been in continuous operation for more than 340 years, which ranks it as one of the oldest in the world. The company began as a fur-trading enterprise, thanks to an English royal charter in back in 1670 during the reign of King Charles II. These days, Hudson’s Bay Company owns and operates retail stores throughout Canada and the United States.

In addition to his trade in furs, Ross collected specimens for the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Ross is responsible for giving the goose that now bears his name one of its early common names – the Horned Wavy Goose of Hearne. I wonder why that never caught on?

Ross repeatedly insisted that this small goose was a species distinct from the related and larger lesser snow goose and greater snow goose. His vouching for this small white goose eventually convinced other experts that this bird was indeed its own species.

Ross was born in Ireland in 1827. He died in Toronto, Ontario, in 1874. He was described by other prominent early naturalists as “enthusiastic” and “a careful observer” in the employ of Hudson’s Bay Company. When John Cassin gave the Ross’s Goose its first scientific name of Anser rossii in 1861, he paid tribute to the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Ross.

•••

Some other notable waterfowl have already been spotted this winter. A Northern pintail has been observed at Erwin Fishery Park. As winter extends its icy grip farther north, more waterfowl are likely to migrate through the region. Keep an eye on rivers, ponds and lakes to see what unusual waterfowl might be visiting.