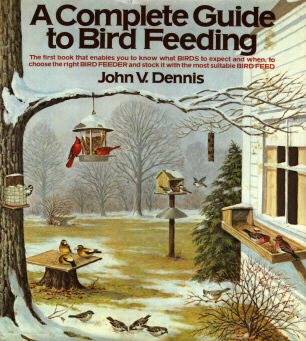

The Northern cardinal, a familiar backyard bird in many sections of the United States, is a perfect symbol of the Christmas season.

The shopping days before Christmas are getting fewer, so I hope everyone has had time to find gifts for everyone on their lists. My wish to readers is that everyone gets to enjoy a great holiday that just might also include watching some birds.

Although I hate to see the colorful birds of spring and summer — scarlet tanagers, Baltimore orioles, indigo buntings, rose-breasted grosbeaks — depart every fall, the winter season offers some compensation.

Often, when we think of the birds of the winter season, our thoughts focus on some of the less-than-colorful feeder visitors — the brown sparrows and wrens, the black and white chickadees and the drab American goldfinches, so unlike their summer appearance.

Photo by Skeeze/Pixabay.com • A male Northern cardinal lands on a snowy perch. Cardinals are perfect symbols for the Christmas season with their bright red plumage.

There’s one bird, however, that makes an impression in any season. The Northern cardinal, especially the brilliant red male, stands out against a winter backdrop of snow white, deep green or drab gray. On a recent snowy afternoon, I spent some time watching a pair of Northern cardinals from my window. Cardinals are wary birds. They make cautious approaches to feeders, never rushing to the seed in the manner of a Carolina chickadee or tufted titmouse.

The Northern cardinal belongs to a genus of birds known as Cardinalis in the family Cardinalidae. There are only two other species in this genus, and they range across North America and into northern South America. The two relatives are the pyrrhuloxia, or Cardinalis sinuatus, a bird of the southwestern United States, and the Vermilion Cardinal, or phoeniceus, a bird found in Colombia and Venezuela.

Photo by U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service • The Pyrrhuloxia, or desert cardinal, is a counterpart to the Northern cardinal in the American southwest.

Two other South American birds — red-crested cardinal and yellow-billed cardinal — are more closely related to tanagers than to our familiar Northern cardinal. Both the Northern cardinal and red-crested cardinal have been introduced into the state of Hawaii, so two non-native birds from different parts of the globe are now resident in the Aloha State.

Photo by Pixabay.com • A red-crested cardinal forages on a sandy beach. This bird has been introduced to such exotic locations as Hawaii.

Over the years, the Northern cardinal has also become associated with the Christmas season. How many Christmas cards have you received this holiday season with a cardinal featured in the artwork? I’d wager that at least a few cards in any assortment of holiday greetings will feature the likeness of a bright red cardinal.

Cardinals, also known by such common names as redbird and Virginia nightingale, are easily recognized backyard birds. I never tire of observing these colorful birds. Cardinals are easily lured to any backyard with plentiful cover to provide a sense of security and a generous buffet of sunflower seed.

Photo by Skeeze/Pixabay.com • A female Northern cardinal lands on a deck railing. Female cardinals are not as brightly colorful as males, but they do have their own subtle beauty.

Cardinals accept a wide variety of food at feeders. Sunflower seed is probably their favorite, but they will also sample cracked corn, peanuts, millet, bakery scraps and even suet. The cardinal is also one of only a few birds that I have noticed will consistently feed on safflower seed.

While we may get the idea that cardinals feed largely on seed, that is a misconception based on our observation of the birds at our feeders. When away from our feeders, cardinals feed on insects and fruit, including the berries of mulberry, holly, pokeberry, elderberry, Russian olive, dogwood and sumac.

There’s no difficulty in identifying a cardinal. The male boasts crimson plumage, a crest, a black face and orange bill. The female, although less colorful, is also crested. Female cardinals are soft brown in color, with varying degrees of a reddish tinge in their feathers, particularly in their wings. Immature cardinals resemble females except young cardinals have dark bills.

Cardinals are a widespread species, ranging westward to the Dakotas and south to the Gulf Coast and Texas. The southeastern United States was once the stronghold of the cardinal population. In the past century, however, cardinals have expanded their range into New England and Canada.

The familiar Northern Cardinal is not the only bird to bear the name cardinal. Others include the yellow cardinal of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, the vermilion cardinal of Colombia and Venezuela, and the red-crested cardinal, a songbird native of South America that has also been introduced to Puerto Rico and Hawaii.

Photo by Bryan Stevens • Northern cardinals will visit feeders stocked with sunflower seeds at any season.

At feeders, cardinals mingle with a variety of other birds. Cardinals are common visitors to backyard feeders. For such a bright bird, the male cardinal can be surprisingly difficult to detect as he hides in the thick brush that conceals his presence. Cardinals are nervous birds, however, and usually betray their presence with easily recognized chip notes. Their preference for dense, tangled habitat is one they share with such birds as brown thrashers, Eastern towhees, Carolina wrens and song sparrows. In general, however, cardinals directly associate only with their own kind. Cardinals will form loose flocks during the winter, but these flocks are never as cohesive as those of such flocking birds as American goldfinches. Cardinals are more often observed in pairs.

It’s not surprising that such a popular bird has also become associated with many trappings of the Christmas season.

“You see cardinals on greeting cards, stationery, paper plates, paper napkins and tablecloths, doormats, light switch plates, candles, candle holders, coffee mugs, plates, glasses, Christmas tree ornaments and lights, bookmarks, mailboxes, Christmas jewelry,” writes June Osborne in her book The Cardinal. “And the list goes on. Cardinals have become an integral part of the way that many people celebrate the holiday season.”

I can be included among such people. My Christmas decorations include an assortment of cardinal figurines and ornaments. There are other birds — doves and penguins for example — associated with the holiday season, but for me the holidays magnify the importance of one of my favorite birds. The cardinal, in its festive red plumage, appears made to order for a symbol of the holiday season.

Photo by Bryan Stevens • Northern cardinals are a favorite for makers of Christmas ornaments.

There’s additional evidence to put forward as testimony to the popularity of the Northern cardinal. It’s the official state bird of seven states: Virginia, North Carolina, West Virginia, Ohio, Illinois, Indiana and Kentucky. Only the Northern mockingbird, which represents five states as official state bird, even comes close to the Northern cardinal in this respect.

Even once the holidays are past, there’s nothing like a glimpse of a Northern cardinal to add some cheer to a bleak winter day. Simply add some black oil sunflower seeds to your feeders to welcome this beautiful bird to your yard.

Photo by Bryan Stevens • A male Northern cardinal visits a feeder on a snowy afternoon.