Photo by Bryan Stevens • Raptors, like this Red-tailed Hawk, proved plentiful on count day. Broad-winged Hawk, a relative of the Red-tailed Hawk, even set a new record for most individuals found.

The 49th consecutive Elizabethton Fall Count was held Saturday, Sept. 29, with 50 observers in 13 parties covering parts of five adjacent counties.

According to count compiler Rick Knight, a total of 127 species were tallied (plus Empidonax species), slightly higher than the average of the last 30 years, which was 125. The all-time high was 137 species in 1993.

Two very rare species were found: Purple Gallinule at Meadowview Golf Course in Kingsport and Black-legged Kittiwake on South Holston Lake. The kittiwake had been found Sept. 27 and lingered until count day.

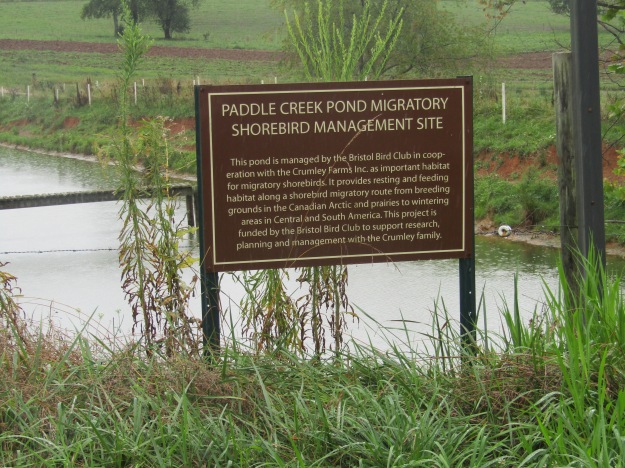

Shorebird habitat was scarce due to high water levels at most sites, thus only one species was found (other than Killdeer).Broad-winged Hawks were numerous, part of a notable late flight likely due to unfavorable weather conditions preceeding the count.

Warblers were generally in low numbers, although 23 species were seen. No migrant sparrows had arrived yet. Blackbirds, too, were scarce. Some regular species were tallied in record high numbers, likely due to the above average number of field parties.

Photo by Bryan Stevens • Wild Turkeys and Ruffed Grouse were found on this year’s count, but participants failed to locate any Northern Bobwhites.

The list of species follows:

Canada Goose, 781; Wood Duck, 79; Mallard, 345; Blue-winged Teal, 110; Com. Merganser, 2; Ruffed Grouse, 2; and Wild Turkey, 56.

Pied-billed Grebe 32; Double-crested Cormorant, 78; Great Blue Heron, 49; Great Egret, 2; Green Heron, 2; and Black-crowned Night-Heron, 5.

Photo by Bryan Stevens • Several species of herons and egrets were located, including Black-crowned Night Heron.

Black Vulture 71; Turkey Vulture 203; and Osprey, 27. This represented a new record for the number of Osprey found on this count.

Bald Eagle 8; Northern Harrier, 1; Sharp-shinned Hawk, 3; Cooper’s Hawk, 9; Red-shouldered Hawk, 6; Broad-winged Hawk, 321; (most ever on this count) and Red-tailed Hawk, 19.

Virginia Rail 1; Purple Gallinule, 1; Killdeer, 43; Spotted Sandpiper, 1; Black-legged Kittiwake, 1; Caspian Tern, 1; and Common Tern, 2.

Rock Pigeon, 597; Eurasian Collared-Dove, 2; Mourning Dove, 330; Yellow-billed Cuckoo, 4; E. Screech-Owl, 24; Great Horned Owl, 10; Barred Owl, 5; Northern Saw-whet Owl, 1; and Common Nighthawk, 1.

Chimney Swift, 481; Ruby-throated Hummingbird, 31; Belted Kingfisher, 32; Red-headed Woodpecker, 5; Red-bellied Woodpecker, 92; Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, 5; Downy Woodpecker, 59; Hairy Woodpecker, 12; Northern Flicker, 67; Pileated Woodpecker, 54; American Kestrel, 13; and Merlin, 2. The figures for Red-bellied and Pileated Woodpeckers mark new high counts for these two species.

Photo by Bryan Stevens • A record number of Red-bellied Woodpeckers were found on this year’s Fall Bird Count.

Eastern Wood-Pewee 15; Empidonax species, 2; Eastern Phoebe, 79; Eastern Kingbird, 9; White-eyed Vireo, 1; Yellow-throated Vireo, 2; Blue-headed Vireo, 21; Philadelphia Vireo, 3; Red-eyed Vireo, 4; Blue Jay, 646; American Crow, 364; and Common Raven, 1.

Northern Rough-winged Swallow, 3; Tree Swallow, 465; Barn Swallow, 1; and Cliff Swallow, 3.

Carolina Chickadee, 177; Tufted Titmouse, 133; Red-breasted Nuthatch, 4; White-breasted Nuthatch, 71; Brown Creeper, 1; House Wren, 4; Winter Wren, 1; and Carolina Wren, 218. Both Tufted Titmouse and White-breasted Nuthatch were found in record numbers, as was the Carolina Wren, too

Golden-crowned Kinglet, 8, Eastern Bluebird, 187; Gray-cheeked, Thrush 12; Swainson’s Thrush, 46; Wood Thrush, 9; American Robin, 591; Gray Catbird, 64; Brown Thrasher, 23; and Northern Mockingbird, 111; European Starling 1,226; and Cedar Waxwing, 294. The number of Gray Catbirds set a new record for the species.

Worm-eating Warbler 1; Northern Waterthrush, 1; Black-and-white Warbler, 7; Prothonotary Warbler, 1; Tennessee Warbler, 42; Orange-crowned Warbler, 2; Kentucky Warbler, 2; Common Yellowthroat, 9; Hooded Warbler, 7; American Redstart, 16; Cape May Warbler, 6; Northern Parula, 8; Magnolia Warbler, 18; Bay-breasted Warbler, 15; Blackburnian Warbler, 8; Yellow Warbler, 1; Chestnut-sided Warbler, 1; Black-throated Blue Warbler, 4; Palm Warbler, 63; Pine Warbler, 11; Yellow-throated Warbler, 1; Prairie Warbler, 1; and Black-throated Green Warbler, 7.

Photo by Bryan Stevens • Participants found a total of 23 different species of warblers, including American Redstarts.

Eastern Towhee, 66; Chipping Sparrow, 94; Field Sparrow, 16; Song Sparrow, 97; and Dark-eyed Junco, 42.

Summer Tanager 2; Scarlet Tanager, 11; N. Cardinal, 149; Rose-breasted Grosbeak, 125; and Indigo Bunting, 14.

Bobolink, 2; Red-winged Blackbird, 132; Eastern Meadowlark, 7; Common Grackle, 8; Brown-headed Cowbird, 5; House Finch, 41; Pine Siskin, 11; American Goldfinch, 220; and House Sparrow, 69.

Photo by Bryan Stevens • American Goldfinches were among the smaller songbirds found during the annual Fall Bird Count.