Some interesting waterfowl have spent at least part of the winter at the pond at Erwin Fishery Park. A male redhead, a female Northern shoveler and a female ring-necked entertained area birders, as did other waterfowl such as hooded merganser and Ross’s goose. A solitary female green-winged teal has lingered for several weeks, showing considerable expertise at not drawing attention to herself.

Green-winged teal belong to the group of ducks known as dabblers, which includes the familiar mallard as well as species like American wigeon, Northern pintail, gadwall and mallard. The dabbling ducks generally feed in shallow water.

In North America, there are two other close relatives of the green-winged teal: blue-winged teal and cinnamon teal. I’ve seen the green-winged and blue-winged at many locations in the region. I saw my only cinnamon teal during a trip to Utah and Idaho in 2003.

Blue-winged teal often migrate through the region in small flocks in early spring and again in late summer and early fall. The cinnamon teal is not as abundant in North America as other dabbling ducks. Many of these teal nest around the Great Salt Lake in Utah, although I saw the cinnamon teal that counted as my “life list” bird at the Bear Lake National Wildlife Refuge in southeast Idaho in October of 2003.

The male cinnamon teal is a striking duck with bright reddish plumage. The female’s plumage is a much duller brown. In size, it’s the largest of the North American teal species and can weigh 14 ounces. In contrast, blue-winged teal weigh 13 ounces while the green-winged teal only tips the scales at 11 to 12 ounces. However, some individual green-winged teal may only weigh five or six ounces. It’s helpful to observe teal in the company of geese or other ducks. In direct comparison, it’s easy to observe how incredibly tiny these birds are compared to their relatives.

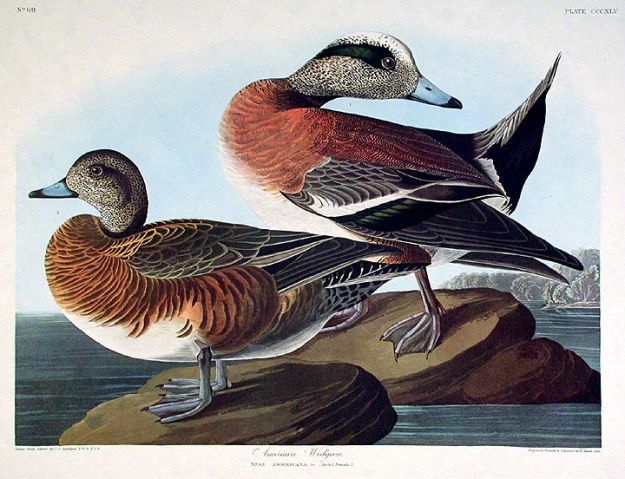

In fact, according to the Ducks Unlimited website, the green-winged teal is the smallest of the North American dabbling ducks. The website describes the male green-winged teal as having a chestnut head with an iridescent green to purple patch extending from the eyes to the nape of the neck. The chest is pinkish-brown with black speckles, and the back, sides and flanks are vermiculated gray, separated from the chest by a white bar. The wing coverts are brownish-gray with a green speculum.

As is the case with many ducks, females, or hens, are much duller in plumage than the males, or drakes. Green-winged teal hens are brown with a yellowish streak along the tail. Like the male, she shows green wing patches in the secondary wing feather. These patches are known as speculums, but these may be not be readily visible unless the bird’s in flight.

Photo by U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service • A green-winged teal drake is a small but colorful waterfowl.

The green-winged teal’s global population stood at only 772,000 birds in 1962, but this teal’s population has grown steadily in the subsequent decades. The green-winged teal can be found during the summer nesting season from Alaska, across Canada, into the Maritime Provinces of Canada, south into central California, Utah, Colorado, Nebraska, Minnesota and Wisconsin.

Green-winged teal hens are good mothers. They lay a clutch of six to nine eggs, which they incubate for about 22 days. She likes to conceal her nest, often choosing a location that offers dense cover that may form a sheltering canopy over the nest site.

During winter, many green-winged teal migrate to coastal areas of Texas and Louisiana, but some will keep going as far south as Central America, the Caribbean, and even into northern South America. A few individuals may, as did the small hen at Erwin Fishery Park, stop and linger at ponds, rivers or other wetlands through the southeastern United States.

Photo by U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service • A male cinnamon teal forages in a wetland. These striking ducks are a species of waterfowl that is usually only found in the western half of the United States.

Like other dabbling ducks, green-winged teals search for aquatic vegetation, which comprises the majority of their diet. These ducks also feed on some insects, crustaceans and other invertebrates. Pollution of wetlands and ingestion of discarded lead pose serious perils, but as a species this smallest of the dabblers is not considered particularly vulnerable. The green-winged teal is hunted as a game bird through most of its range.

Photo by U.S Fish & Wildlife Service • In this photo of a hen and drake green-winged teal, it’s easy to see the green patch, or speculum, in the female’s wing. It’s the only spot of color in her brown-gray plumage.

Look for green-winged teal and other ducks on farm ponds or similar bodies of waters in city parks. If conditions are to their liking, these ducks will often winter at such locations in the region. The ponds along the walking trails in Erwin, Tennessee, have been a good place for many years to look for green-winged teal during the winter season. They are more shy than other ducks. If pressed too closely, this small duck is likely to take flight. Enjoy through binoculars from a comfortable distance.

So far, the green-winged teal at the Fishery Park pond has led a solitary existence. The male redhead, however, has been seen recently cavorting with a newly-arrived redhead hen. This pair of ducks has engaged in typical mating displays appropriate to their species and are usually inseparable.

Once time arrives for them to depart for their summer nesting grounds, they will likely make the migratory flight together.

Godspeed to them.