A century ago this week, a caged bird died in Cincinnati, Ohio. However, this was not simply a case of an untimely death of a beloved family pet. Instead, that bird represented the last of its kind.

The bird belonged to the Psittacidae, a family of tropical birds that includes macaws, parrots, caiques, amazons and parrotlets. The bird, a male named Incas, was the last captive Carolina parakeet (the only species of parrot native to the eastern United States) in existence when he died at the Cincinnati Zoo on Feb. 21, 1918, in the same aviary where Martha, the last passenger pigeon, had died four years earlier.

The demise of Incas came about a year after the death of his mate, who had been named Lady Jane by their zookeepers. In a time before the forces of social media and round-the-clock mass media, the death of Incas likely went unnoticed by other than a few people.

If few noticed the passing of Incas at the time, surely today we can mourn the loss of one of the most abundant birds to ever roam the continent. Few people even realize that North America was once home to its own species of parakeet. A few individuals — all that remained of once massive flocks of colorful, noisy native parakeets — made it into the 20th century. Despite the death of Incas in 1918, the Carolina parakeet as a species was not officially declared extinct until 1939. It was a classic example of going out with a whimper, not a bang, when the entire population of the Carolina parakeet crashed suddenly and for reasons still not fully understood.

For instance, large flocks of these birds still flew free until the final years of the 1800s, but in the first decade of the 1900s, these flocks disappeared. The only other native parrot — the thick-billed parrot of the American southwest — no longer flies north of the Mexican border. An attempt to re-introduce this parrot to Arizona in the 1980s ended in disappointing failure. Of course, thick-billed parrots still fly free south of the border.

It would be wonderful to have native parrots still flying free. The extinct Carolina parakeet ranged throughout the eastern United States, including the states of Virginia, Tennessee and North Carolina. These parrots strayed on occasion as far north as Wisconsin and New York and ranged as far west as Colorado. Florida provided a stronghold for this colorful species, which also made its last stand in the Sunshine State. The last flock of thirteen wild birds was documented in Florida in 1904.

These birds have attracted attention since the arrival of the first Europeans. English explorer George Peckham mentioned the presence of Carolina parakeets in an account he wrote of his 1583 expedition in Florida. In the 1700s, English naturalist Mark Catesby described the species for science in a two-volume work titled “The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands.”

The parrots were evidently numerous, often encountered in large flocks. Few early naturalists attempted to properly study them, resulting in a sad dearth of knowledge. Much of what we do know is quite intriguing. The diet of these parakeets made them toxic, as early naturalist and artist John James Audubon observed when cats sickened and died after dining on fresh parakeets. One of the parakeet’s favorite foods — cockleburs —imparted the toxicity into the flesh of the birds.

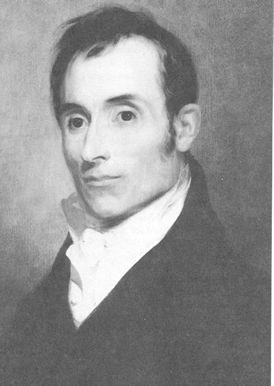

Alexander Wilson

An unusual empathy and loyalty may have contributed to the downfall of the species. Early naturalist Alexander Wilson wrote of an 1808 encounter with a large flock of these parakeets. After noting how the bird covered almost every twig in a tree, Wilson raised a gun and shot several of the birds. Some of the shot birds were only wounded. “The whole flock swept repeatedly around their prostrate companions, and again settled on a low tree, within twenty yards of the spot where I stood,” Wilson wrote. “At each successive discharge, although showers of them fell, yet the affection of the survivors seemed rather to increase.”

The same tendency to rally to the side of fallen companions made Carolina parakeets easy targets for people capturing them in the late 1800s for the exotic pet trade. This flocking together and unwillingness to abandon wounded members made the birds easy targets when farmers shot them. It certainly didn’t help matters that the parakeets were also hunted for their brightly colored feathers, which were used to adorn women’s hats. It remains unclear what exactly annihilated a once abundant bird, although it was likely a combination of all of the aforementioned factors.

Changes to the landscape encouraged the parakeets to shift their diet from weed seeds to cultivated fruit, which won them the ire of farmers. Logging of extensive forests may have impacted their numbers, too. Experts have even theorized that the parakeets fell victim to some sort of epidemic spread by domestic fowl.

Painting by Alexander Wilson of a Carolina Parakeet.

If only the dawning of a more environmentally aware age had arrived slightly sooner, the Carolina parakeet might have been saved along with species like the bald eagle and whooping crane. This native parakeet, if it had endured, might today be considered an ordinary backyard bird jostling for space at your feeders with birds like blue jays and purple finches.

Incas and his fellow Carolina parakeets may be gone, but they’ve not been forgotten. Their story is a reminder of why it remains crucial to protect all birds. Let that devotion to preservation be the legacy of America’s lost parakeets.

•••••

Bryan Stevens lives near Roan Mountain, Tennessee. To learn more about birds and other topics from the natural world, friend Stevens on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/ahoodedwarbler. If you have a question, wish to make a comment or share a sighting, email ahoodedwarbler@aol.com.

Photo by Bryan Stevens • Although protections came too late to help the Carolina Parakeet, laws like the Endangered Species Act did save birds like the Bald Eagle from possible extinction.