Considering the bright finery worn by some of the more colorful spring arrivals, I could hardly blame you if the return of the Eastern phoebes escaped your notice. In comparison with vibrant birds like rose-breasted grosbeak, ruby-throated hummingbird, scarlet tanager and yellow warbler, the Eastern phoebe is downright drab.

Photo by Bryan Stevens This fledgling Eastern phoebe waits patiently on a branch for a parent to bring it a morsel of food. Phoebe-Baby

Nevertheless, this member of the flycatcher clan has earned itself a favorite spot in the hearts of many a birdwatcher. It’s one of those birds that even beginning birders find surprisingly easy to recognize and identify. While it may not have a dramatic plumage pattern to hint at its identity, the Eastern phoebe is quite at home around human dwellings and comes into close contact with people going about their daily routines. Rather tame — or at least not too bothered by close proximity with humans — the Eastern phoebe has one behaviorism that sets it apart from all the other similar flycatchers. When this bird lands on a perch, it cannot resist a vigorous bobbing of its tail. Every time that a phoebe lands on a perch, it will produce this easily recognized tail wag. It’s a behavior that makes this bird almost instantly recognizable among birders with the knowledge of this behavioral trait.

The Eastern phoebe is also an enthusiastic springtime singer, and the song it chooses to sing is an oft-repeated two-syllable call “FEE-bee” that provides the inspiration for this bird’s common name.

The Eastern phoebe, known by the scientific name of Sayornis phoebe, has two relatives in the genus Sayornis. The genus is named after Thomas Say, an American naturalist. The Eastern phoebe’s close relatives include the black phoebe and Say’s phoebe. The black phoebe ranges throughout Oregon, Washington and California and as far south as Central and South America. As its name suggests, this bird has mostly black feathers instead of the gray plumage of its relatives. The Say’s phoebe, also named for the man who gave the genus its name, is the western counterpart to the Eastern phoebe.

Since they belong to the vast family of New World flycatchers, it’s probably no surprise that these phoebes feed largely on insects. The birds will often perch patiently until an insect’s flight brings it within easy range. A quick flight from its perch usually allows the skillful bird to return with a morsel snatched on the wing. In the winter months, the Eastern phoebe also eats berries and other small fruit.

Phoebes are fond of nesting on human structures, including culverts, bridges and houses. With the latter, they were once known for their habit of placing their nests under sheltering eaves. At my home, a pair of Eastern phoebes often chooses to nest on the wooden rafters in my family’s garage. Phoebes also like to reside near a water source, such as a creek, stream or pond.

Although the species is migratory, a few hardy individuals will usually try to tough out winters in the region. The others that depart in the autumn will migrate to the southern United States and as far south as Central America. On some rare occasions, Eastern phoebes have flown far off their usual course and ended up in western Europe. I can usually count on Eastern phoebes returning to my home in early March, making them one of the first migrants to return each year. Their arrival rarely goes unnoticed since the males tend to start singing persistently as soon as they arrive.

Photo by Bryan Stevens An Eastern Phoebe perches on a sign at Roan Mountain State Park in Roan Mountain, Tennessee.

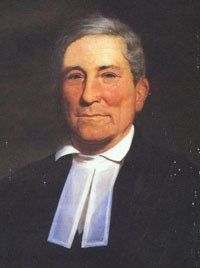

A few weeks ago I wrote about opportunities to take part in citizen science projects for the benefit of birds. The concept of ordinary citizens making a difference in scientific discovery isn’t a new one. More than two centuries ago, one of the most influential birders in history and the namesake of the National Audubon Society used Eastern phoebes to help add to the knowledge of bird migration.

John James Audubon, an early naturalist and famed painter of North America’s birds, conducted an experiment with some young phoebes that represents the first-ever bird banding in the United States of America. His novel experiment, which he carried out in 1803, involved tying some silver thread to the legs of the phoebes he captured near his home in Pennsylvania. He wanted to answer a question he had about whether birds are faithful to home locations from year to year. The following year Audubon again captured two phoebes and found the silver thread had remained attached to their legs. Today ornithologists still conduct bird banding to gather information on birds and the mystery of their migrations.

So, that pair of phoebes that returned to your backyard this spring — they just might be the same ones that have spent past summer seasons providing you with an enlightening glimpse into their lives.

••••••

To learn more about birds and other topics from the natural world, friend Bryan Stevens on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/ahoodedwarbler. He is always posting about local birds, wildlife, flowers, insects and much more. If you have a question, wish to make a comment or share a sighting, email ahoodedwarbler@aol.com.