As the calendar moves into the months of October and November, migrating waterfowl will replace the exodus of songbirds that evacuate the North American continent every fall in preparation for their winter season in the tropics. The umbrella term of waterfowl can include such birds as ducks, geese, loons and grebes.

Photo by Bryan Stevens • This pied-billed grebe stranded itself on a wet lawn during fall migration. A grebe’s legs are positioned so far back on their bodies that grebes have difficult walking on land. Once released in a pond, the grebe was able to take flight and continue its migration.

That last family keeps one of the lowest profiles among the grouping of birds lumped together as waterfowl. Worldwide, there are 22 species of grebes. This family also includes three extinct species — Alaotra grebe, Atitlán grebe and Colombian grebe.

Many people are unaware of the grebes. After all, they are oddball birds with not a lot in common with other waterfowl such as loons and ducks. In eastern Tennessee, southwestern Virginia and western North Carolina, the pied-billed grebe is the most likely member of the grebe family to come into contact with humans. The pied-billed grebe’s scientific name, Podilymbus podiceps, can be roughly translated as “rear-footed diver.” The reference is to the fact that this grebe, as well as others of its kind, have their feet positioned so far back on their bodies that movement on land is difficult and awkward.

The pied-billed grebe has inspired a variety of other common names, including American dabchick, dabchick, Carolina grebe, devil-diver, dive-dapper, hell-diver, pied-billed dabchick, pied-bill, thick-billed grebe and water witch, all of which reflect this grebe’s almost exclusively aquatic lifestyle.

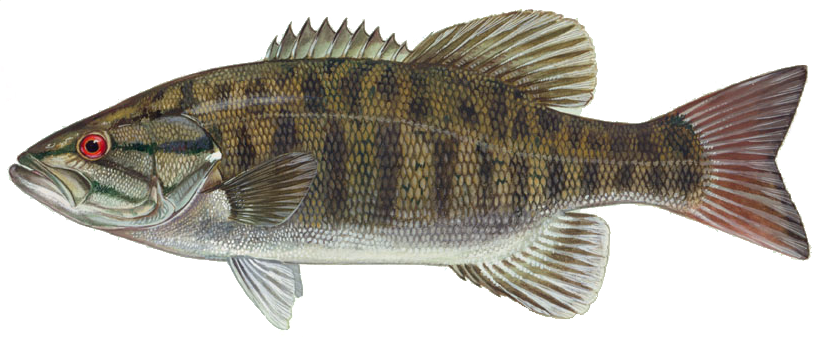

The pied-billed grebe is a world-class survivor. Already a member of an ancient family of birds, this species has outlasted the others in its genus. The Atitlán grebe, which was also known as the giant grebe, went extinct around 1989 after a series of catastrophic setbacks, including a devastating earthquake and the introduction of smallmouth and largemouth bass to Lake Atitlán in Guatemala. The bass consumed the prey this grebe needed for its survival, and large bass occasionally ate young grebes.

Bass introduced into Lake Atitlán consumed the small fish that the Atitlán Grebe required as a food source. Large bass also ate young grebes.

These birds range in size from the least grebe, which weighs only about six ounces, to the great grebe, which can tip the scales at four pounds. North American grebes include red-necked grebe, horned grebe, eared grebe, Clark’s grebe and Western grebe. In extreme southern Texas, birders can find least grebes in suitable wetland habitats.

With the exception of the least grebe, I’ve seen all of North America’s grebes. During visits to Utah in 2003 and 2006, I observed the sleek, long-necked Clark’s grebe and Western grebe. On a 2006 trip to Utah, I visited Antelope Island State Park and observed tens of thousands of Eared Grebes gathered on the Great Salt Lake for the nesting season. In Tennessee, one of the most reliable locations to find eared grebes is from viewing areas at Musick’s Campground on South Holston Lake, where a small number of these grebes have wintered for many years.

An unusual February fallout back in 2014 resulted in equally unusual numbers of red-necked grebes on area lakes, rivers, and ponds. I’d previously observed this grebe on Boone Lake, South Holston Lake and Watauga Lake in northeast Tennessee.

Photo by Bryan Stevens • A Red-necked Grebe mixes with Mallards at a pond on the campus of Northeast State Community College in Elizabethton.

Grebes are prone to landing on glistening surfaces — lawns, asphalt parking lots and even paved roads — during migration flights, especially at night during heavy rain. A serious problem arises when the grebe, with those rear-positioned feet, finds itself stranded, unable to take flight again without a paddling run across the surface of a body of water.

One of these strandings was recounted in Rick Knight’s book, The Birds of Northeast Tennessee. On Feb. 13, 1994, a red-necked grebe grounded itself with one of these crash landings onto a parking lot in Elizabethton, Tennessee. The fortunate grebe received a human-assisted rescue, being transported to a small lake near the town for release.

In November of 2011, a neighbor delivered a bird that had landed in his yard and could not take flight. The bird, put into a cardboard box for its own safety, didn’t appear to have any injuries. Once I saw the bird, I realized it was a pied-billed grebe. We released the bird on my fish pond, where the grebe dived and swam extensively before resting for a long period on a muddy edge of the pond. Overnight, the grebe disappeared. I believe the grebe took flight during the night and continued with its fall migration. The incident remains one of my closest encounters with a grebe.

Photo by Bryan Stevens The pied-billed grebe paddles through the water after it was rescued after a stranding on a lawn.

In the coming weeks and all throughout the winter months, look for pied-bill grebes, as well well as more uncommon grebes like horned grebe and red-necked grebe, on lakes and rivers throughout the region.

•••••

Bryan Stevens lives near Roan Mountain, Tennessee. To ask a question, make a comment or share a sighting, email him at ahoodedwarbler@aol.com.