Photo by Bryan Stevens • A dark-eyed junco, usually a harbinger of wintry weather and snowy days, shells sunflower seeds beneath a feeder.

I wrote my first column about our “feathered friends” on Sunday, Nov. 5, 1995, which means this column will soon celebrate its 23rd anniversary.

This column has appeared on a weekly basis for the last 23 years in a total of five different newspapers, and in recent years it has been syndicated to several more. The column has also been a great conduit for getting to know other people interested birds and birding. I always enjoy hearing from readers, and I hope to continue to do so in the coming years as well. Since February 2014, I’ve also been posting the column as a weekly blog on birds and birding.

I saw my first swamp sparrow of the fall on Oct. 23. Autumn’s a time when many of those so-called “little brown birds,” also known as the sparrows, return to live in the fields, gardens, yards and woodlands around our home. Two of the other anticipated arrivals are white-throated sparrows and dark-eyed juncos.

Photo by Bryan Stevens • Sparrows, like this swamp sparrow, often spend the winter months in fields, woods, and wetlands, sometimes visiting feeders in our homes and gardens.

In fact, that first column I wrote back in 1995 focused on one of the region’s most prevalent winter residents— the dark-eyed junco. Experts place juncos among the varied sparrow family. All juncos are resident of the New World, ranging throughout North and Central America. Scientists are continually debating precisely how many species of junco exist, with estimates ranging from a mere three species to about a dozen species.

Some of the other juncos include the volcano junco, yellow-eyed junco, Chiapas junco, Guadalupe junco, pink-sided junco, Oregon junco and Baird’s junco, which is named in honor Spencer Fullerton Baird, a 19th century American naturalist and a former Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution.

With that introduction and with some revisions I have made through the years, here is that very first column that I ever wrote about birds.

Photo by Skeeze-Pixabay • A dark-eyed junco clings to a snowy perch.

…..

Of all the birds associated with winter weather, few are as symbolic as the dark-eyed junco, or “snow bird.” The junco occurs in several geographic variations.

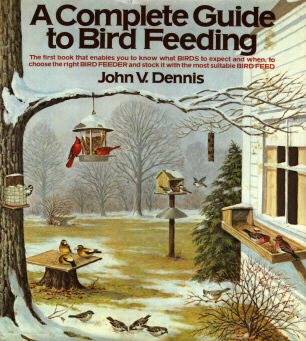

John V. Dennis, author of “A Complete Guide to Bird Feeding,” captures the essence of the junco in the following description: “Driving winds and swirling snow do not daunt this plucky bird. The coldest winter days see the junco as lively as ever and with a joie de vivre that bolsters our sagging spirits.” The dark-eyed junco’s scientific name, hyemalis, is New Latin for “wintry,” an apt description of this bird.

Most people look forward to the spring return of some of our brilliant birds — warblers, tanagers and orioles — and I must admit that I also enjoy the arrival of these birds. The junco, in comparison to some of these species, is not in the same league. Nevertheless, the junco is handsome in its slate gray and white plumage, giving rise to the old saying “dark skies above, snow below.”

Just as neotropical migrants make long distance journeys twice a year, the junco is also a migrating species. But in Appalachia, the junco is a special type of migrant. Most people think of birds as “going south for the winter.” In a basic sense this is true. But some juncos do not undertake a long horizontal (the scientific term) migration from north to south. Instead, these birds merely move from high elevations, such as the spruce fir peaks, to the lower elevations. This type of migration is known as vertical migration. Other juncos, such as those that spend their breeding season in northern locales, do make a southern migration and, at times, even mix with the vertical migrants.

Juncos are usually in residence around my home by early November. Once they make themselves at home I can expect to play host to them until at least late April or early May of the following year. So, for at least six months, the snow bird is one of the most common and delightful feeder visitors a bird enthusiast could want.

Juncos flock to feeders where they are rather mild-mannered — except among themselves. There are definite pecking orders in a junco flock, and females are usually on the lower tiers of the hierarchy. Females can sometimes be distinguished from males because of their paler gray or even brown upper plumage.

Photo by Ken Thomas • A dark-eyed junco perches on some bare branches on a winter’s day.

Since juncos are primarily ground feeders, they tend to shun hanging feeders. But one winter I observed a junco that had mastered perching on a hanging “pine cone” feeder to enjoy a suet and peanut butter mixture.

Dark-eyed juncos often are content to glean the scraps other birds knock to the ground. Juncos are widespread. They visit feeders across North America. The junco is the most common species of bird to visit feeding stations. They will sample a variety of fare, but prefer such seeds as millet, cracked corn or black oil sunflower.

There’s something about winter that makes a junco’s dark and light garb an appropriate and even striking choice, particularly against a backdrop of newly fallen snow.

Photo by Bryan Stevens • Dark-eyed junco nests on high mountain slopes during the summer month. This dark-eyed junco was photographed at Carver’s Gap on Roan Mountain during the summer nesting season.

Of course, the real entertainment from juncos come from their frequent visits to our backyard feeders. When these birds flock to a feeder and begin a furious period of eating, I don’t even have to glance skyward or tune in the television weather forecast. I know what they know. Bad weather is on the way!

•••••

Back when I wrote that original column, juncos often returned each fall in the final days of October or first days of November. In the last few years, however, their arrival times have grown consistently later in November. At times, it takes a serious snowfall to drive these hardy birds to seek out easy fare at my feeders. I’m hoping they’ll return soon. In the meantime, if you want to share your first dark-eyed junco sighting of the fall, I’d love to hear from you. If you want to share a sighting, have a question or wish to make a comment, email ahoodedwarbler@aol.com.

Photo by Bryan Stevens • A female dark-eyed junco scrambles for sunflowers seeds in the snow.