I always feel some reluctance and regret when I turn the calendar page from August to September.

I don’t have anything against fall – it’s my favorite season. But I know that our ruby-throated hummingbirds, which returned only five months ago in early April, will soon be departing.

It won’t be only the hummingbirds. Warblers, orioles, tanagers and other migrants will also fly south to spend the winter season somewhere more hospitable.

Most of the hummingbirds that visited our gardens over the summer are getting ready to migrate back to their winter homes in Central America.

I’m seeing only a few adult male hummingbirds with the namesake red throat. They are outnumbered by females and young hummingbirds that hatched in late spring and throughout the summer. It’s fun to watch young hummingbirds. They often have something to prove. In many ways, they’re even more feisty than adult birds.

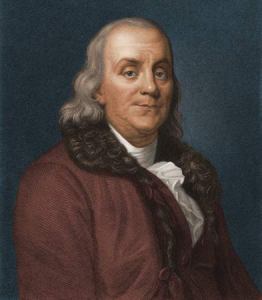

Photo by Bryan Stevens • A male ruby-throated hummingbird perches at a feeder for a sip of sugar water.

In any given year, the numbers of hummingbirds passing thorough is going to fluctuate. Some years, these tiny flying gems will be present in good numbers on an almost daily basis. Other years, hummingbirds can become quite scarce.

I usually enjoy my best hummingbird numbers in the fall as these little birds begin their leisurely journey back south. Late August and the month of September is usually a great time to watch hummingbirds.

During August, the feeders at my home and my mother’s home saw a great deal of activity. Blooms of wildflowers and cultivated flowers also attracted them. Earlier in the summer the hummingbirds went gaga for the crocosmia blooms and the flowering bee balm. For the past month, the tube-shaped flowers of orange jewelweed has kept them coming back for more.

The New World is home to about 360 species of hummingbirds. We’ve expended many adjectives in finding names of them all. Sometimes, words fail. Mere adjectives are somewhat inadequate in providing common names for many of the world’s more hummingbirds, but that doesn’t keep us from trying to give descriptive names to each hummingbird species. For instance, we have the beautiful hummingbird of Mexico; the charming hummingbird of Costa Rica and Panama; the festive coquette of northwestern South America; and the magnificent hummingbird of the southwestern United States.

Other names are even more elaborate and occasionally outlandish, such as the white-tufted sunbeam of Peru; the violet-throated metaltail of Ecuador; the violet-throated starfrontlet of Peru and Bolivia; the hyacinth visorbearer of Brazil; and the rainbow-bearded thornbill of Colombia and Ecuador.

As for our own ruby-throated hummingbirds, wish them well as they begin that long trek back to their wintering grounds. For the young birds, this will be their first epic crossing of the Gulf of Mexico, something the species must do twice a year to get to and from their summer home in eastern North America.

•••

Bryan Stevens has written about birds, birding and birders since 1995.